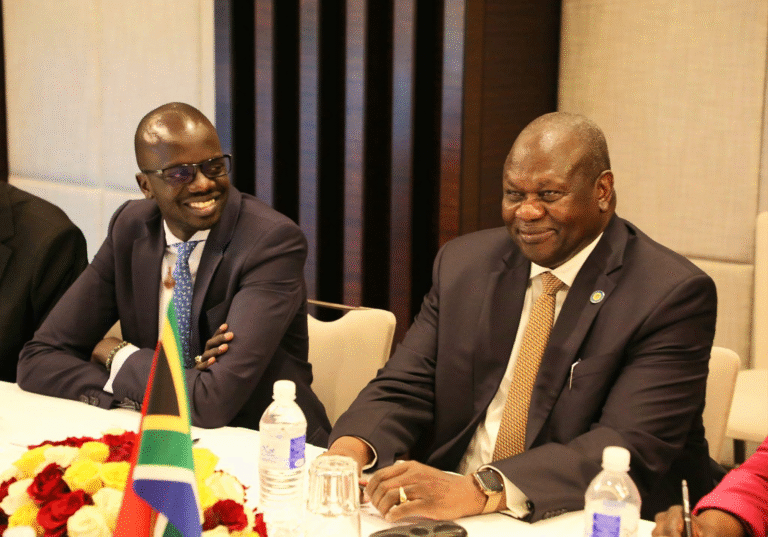

Juba | Thursday, South Sudan’s First Vice President, Dr. Riek Machar, has been suspended from office and charged with treason, crimes against humanity, and murder, igniting a new constitutional and political crisis in the fragile transitional government.

President Salva Kiir issued the suspension late Thursday through a decree aired on national broadcaster SSBC. The order also named Petroleum Minister Puot Kang Chuol and cited Articles 101(D) of the Transitional Constitution (2011, as amended) and Section 38(1) of the Interpretation of Laws Act (2006) as legal grounds for temporarily removing the officials from office pending trial.

The charges relate to a March 2025 clahses between White Army and SSPDF in Nassir, Upper Nile State, which killed more than 250 government troops. Authorities allege the assault was carried out by the White Army, a Nuer militia reportedly under Machar’s influence. Justice Minister Joseph Geng Akech described the incident as a serious breach of international humanitarian law, citing mutilation of corpses, targeting of civilians, and attacks on aid workers. Machar and seven allies now face criminal prosecution for treason and mass atrocities.

Constitution vs. Peace Deal: A Legal Standoff… While the presidency defends the suspension as constitutionally justified, Machar’s allies and independent observers point to a direct contradiction with the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), which explicitly protects the tenure of the First Vice President throughout the Transitional Period.

According to Section 1.7 of the Agreement, the position of First Vice President is not merely appointed but guaranteed for the full duration of the transition: “The Chairman of the SPLM/A-IO, Dr. Riek Machar Teny, shall assume the position of the First Vice President of the Republic of South Sudan for the duration of the Transitional Period” (Article 1.7.2, R-ARCSS). The agreement further outlines Machar’s wide-ranging powers, including chairing the Governance Cluster and acting as Commander-in-Chief of SPLM/A-IO forces (Articles 1.7.3.1 to 1.7.3.6). Notably, nowhere in the agreement is there a provision for the president to unilaterally suspend or remove the First Vice President during the transitional period.

This directly contrasts with the president’s move. While the Constitution provides for suspensions in cases involving legal proceedings, the peace deal — which serves as the cornerstone of the current unity government — offers no such discretion. “The First Vice President shall serve for the duration of the transition. His position cannot be vacated by presidential decree unless a vacancy is declared under agreed terms, such as resignation, death, or incapacitation,” a senior legal expert said. The controversy raises urgent questions about the supremacy of laws in South Sudan. Is the 2011 Transitional Constitution, amended for the purposes of the peace deal, the ultimate authority? Or does the R-ARCSS, which restructured the executive into a coalition Presidency, override unilateral constitutional actions?

In Section 1.5.1.2, the peace agreement also explicitly identifies Machar — by name and title — as an indispensable part of the transitional executive. “The Chairman of SPLM/A-IO Dr. Riek Machar Teny shall assume the position of the First Vice President of the Republic of South Sudan” (Article 1.5.1.2, R-ARCSS).

Legal scholars and opposition officials argue that Machar’s suspension not only violates the agreement but undermines the very foundation of the unity government. “The peace agreement is not a political courtesy — it is a binding instrument that created this government,” said one observer. “Undermining it threatens to collapse the entire process.”

Machar, who remains under house arrest, has not made a public statement. The SPLM-IO has not issued a formal response yet as well, but internal sources indicate the party sees the move as a breach of the peace deal and a provocation. With the High Court now expected to review the charges, South Sudan enters a precarious phase. If the suspension is upheld without constitutional or political remedy, it could set a precedent allowing executive overreach during the transitional period.

In the meantime, the country’s political stability — already strained by economic hardship, armed group violence, and humanitarian challenges — hangs in the balance. If the president’s move is allowed to stand, it may effectively neutralize the power-sharing agreement and roll back key safeguards intended to prevent domination by any one party. If reversed, it could call into question the credibility of the legal process against Machar. Either way, South Sudan’s fragile peace is being tested not just in courtrooms — but in the very architecture of its transitional governance.