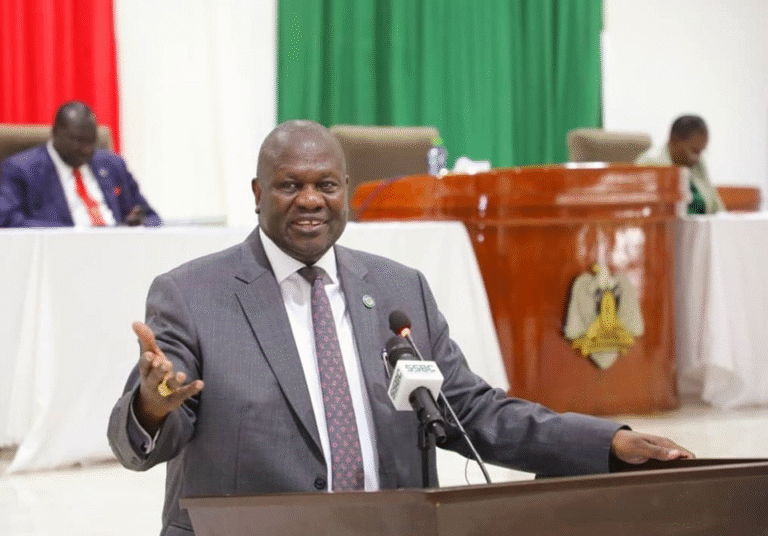

South Sudan’s First Vice President Dr. Riek Machar has been formally charged with treason, crimes against humanity, and murder, months after being detained under house arrest in Juba. The charges stem from his alleged role in orchestrating a brutal attack on SSPDF army barracks in Nasir, Upper Nile State, between 3–7 March 2025, carried out by the White Army, an armed group composed largely of Nuer civilians.

But behind the dramatic press briefing delivered Thursday by newly appointed Justice Minister Dr. Joseph Geng Akech, a deeper legal and constitutional crisis is now emerging: the government’s decision to bypass the Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS), a body mandated by the Revitalized Peace Agreement of 2018 to prosecute exactly these kinds of crimes.

Domestic Trial vs. International Mandate, under Section 5.3 of the R-ARCSS, the Hybrid Court for South Sudan is the judicial mechanism established by the African Union Commission (AUC) to investigate and prosecute serious crimes committed from 15 December 2013 through the end of the transitional period. The agreement states clearly:

“The HCSS shall have primacy over any national courts of the Republic of South Sudan.”

(R-ARCSS, Article 5.3.2.2)

The court’s jurisdiction includes; Genocide, Crimes against humanity, War crimes, and Other serious international crimes, including gender-based violence. Legal analysts say the charges now facing Dr. Machar and seven senior allies—including Petroleum Minister Puot Kang Chol and Deputy Chief of Staff Gen. Gabriel Duop Lam—clearly fall under the HCSS mandate.

“There is no ambiguity here. The agreement is binding, and these alleged crimes are within the scope of the Hybrid Court,” said an international legal expert familiar with South Sudan’s peace process. “Trying Machar in a national court directly undermines the deal signed by Kiir and Machar themselves.”

Government Pushes Ahead, despite this, Justice Minister Geng announced that the trial will proceed in a domestic court, reiterating that all accused have been informed of their rights and will receive a fair trial. He added that the indictment followed a government probe involving 83 individuals, leading to: 21 indictments, 8 formal charges, 13 suspects still at large, and 76 individuals released for lack of evidence.

In Civil Society Responds, Edmund Yakani, head of the Community Empowerment for Progress Organization (CEPO) and a signatory to the 2018 peace agreement, welcomed the move toward accountability—but issued a stern warning. “If this trial happens outside the framework of the HCSS, it sets a dangerous precedent,” Yakani told Unity Times. “The court must not be a tool of political vengeance. It must reflect both legality and legitimacy.” Yakani further called for Public and transparent proceedings, International monitoring, a court that upholds rights, not retribution, and Political Fallout. The case has already intensified divisions within Machar’s SPLM-IO faction. In April, a splinter group led by Peacebuilding Minister Stephen Par Kuol declared an interim leadership aligned with President Kiir—prompting backlash from loyalists, including Deputy Chairman Oyet Nathaniel.

Machar’s looming dismissal as First Vice President—should the trial proceed—could further destabilize an already fragile transitional government struggling to implement key provisions of the peace deal, including: The unification of armed forces, the drafting of a permanent constitution, and the Preparations for national elections. What’s at Stake? By pressing forward with a domestic prosecution, the South Sudanese government now risks not only violating a key international agreement but also jeopardizing the legitimacy of its own judicial process. “Justice must be served—but it must be served lawfully,” said a diplomat from one of the peace guarantor nations. “This is not just about Machar. It’s about whether South Sudan honors the institutions it agreed to.”

As the international community watches closely, the question now facing Juba is not simply whether Dr. Machar is guilty or not, but where he should be tried in his political rival’s house. And the KEY QUESTION remains, Will South Sudan respect its own peace agreement and allow for the establishment of the Hybrid Court to prosecute those accused of atrocity crimes—or will justice be overshadowed by political expediency?